Dr. Graeme, Pest Houses, & Quarantine in Colonial Philadelphia

Quarantine, social distancing, and community spread are very much on our minds these days, but the concepts were not unknown to earlier doctors, including our own Dr. Graeme. Even though disease vectors were not always understood or accurately identified (bad air was often blamed), it was observed that those who avoided the sick escaped disease. While quarantine practices date back to Biblical times, it was in 1374 that Italy enacted the first legal restrictions to prevent the spread of deadly plagues and fevers. The Italian law required that “every plague patient be taken out of the city into the fields, there to die or recover.” Venice, in response to the black death, required ships to anchor for 40 days before coming ashore. The Italian word for forty was “quaranta” – thus the term quarantine. Skipping ahead to the 18th century, Dr. Graeme found himself caught up in the politics of the times as Pennsylvania grappled with establishing a more humane way of quarantining diseased passengers arriving in the port of Philadelphia.

In 1700, a year after yellow fever killed about 220 Philadelphians, the provincial legislature passed the first quarantine law, which was the earliest on record in America, to regulate ships coming into the port. The Act, in part, prohibited any “unhealthy or sickly vessels coming from any unhealthy or sickly place whatsoever,” from coming “nearer than one mile to any of the towns or ports of this province or territories without bills of health.” It also forbade the landing of “such passengers or their goods at any of the said ports or places, until such time as they shall obtain a license for their landing at Philadelphia.”

It seems the law was not actively or effectively enforced until 1720, when Governor William Keith authorized Dr. Patrick Baird to board all ships coming into the port to determine the health of the passengers and crew and prevent them from landing if he saw evidence of sickness or disease. The Council approved this appointment because “without the appointment of such an officer, the health law was lame and defective, and could not answer its first design and intention.” There are no records of Dr. Baird boarding or detaining any ships, or of when he left the position, but in 1728 Dr. Thomas Graeme and Dr. Lloyd Zachary were appointed by Governor Patrick Gordon to visit two sickly vessels, the Dorothy and the Pharaoh, newly arrived from Bristol, England. This is the first recorded instance in Pennsylvania (possibly all of America) of the detention of a sick ship. Doctors Graeme and Zachary found the passengers of the Dorothy to be “seized with a malignant fever, of whom fifeteen died, and good many recovered, and a few still ailing.” Per the law, the Council ordered that the Dorothy remain at least one mile from any towns or ports and that the owner or master provide for some place away from the population that the sick passengers could be removed into the fresh air to recover. Nine days later, and in possession of a certificate of health from Graeme and Zachary, the Dorothy was deemed healthy, but before she was allowed into the port the crew was required to air the bedding and woolen goods, smoke the vessel with tobacco, and wash it with vinegar, which may have taken another ten days or so, but still considerably less than the 40 days required by earlier Italian quarantine.

It wasn’t until ten years later, in 1738, that Philadelphia recorded its second instance of quarantine. The Nancy and the Friendship arrived from the Netherlands and were required to quarantine one mile from the city, but they refused. The captains were arrested and charged 500-pounds as security that they would not land passengers or goods without a license. The ships did not appear to have ailing passengers, but from the swift actions taken by Dr. Graeme it seems they either sailed from a sick port, had suffered disease during the voyage, or on arrival the condition of the passengers or ship seemed unhealthful and likely to breed disease. This was the first recorded instance in Pennsylvania of a ship refusing to obey the quarantine laws.

1738 was also the beginning of the debate to establish a “pest house,” or lazaretto, for the humane quarantine of passengers coming in through the port of Philadelphia. “Lazaretto” is a 16th century Italian word meaning “place set aside for the performance of quarantine.” Immigration from Germany had increased and Governor George Thomas petitioned the Assembly for an alternative to quarantining passengers aboard ship or in whatever accommodations (abandoned houses, barns) could be found away from the populace. The Assembly denied the request, citing the expense. In 1740 they declined to pay Dr. Graeme’s longstanding bill for his work boarding and evaluating incoming ships, claiming that he’d failed to perform his duties and that a lazaretto wouldn’t be needed if he had done his job. This was, in actuality, a political power struggle between the legislative and the executive branches of Pennsylvania’s government: the Assembly contended that the Governor and his Council did not have the right to appoint Graeme to his office without their approval, the Executive felt differently. While the Assembly did not have the authority to remove Graeme, they did have the power of the purse. It is unclear why Graeme had worked so long without submitting a bill (and he was eventually paid 100 pounds), but when it became clear he would not be paid for past or future work, he resigned. It is also not clear when Dr. Zachary had stepped back from working with Dr. Graeme on visitations, but Graeme’s resignation appears to have left the duties of health officer unfulfilled and led to sick ships coming into the port. In 1741 Philadelphia was visited for the second time by yellow fever. In November of that year, the idea of a lazaretto was revisited and this time approved by the Assembly, who also appointed Graeme’s old partner Lloyd Zachary as the Port Physician, which, according to Governor Thomas, they did not have the authority to do. To resolve the dispute, Governor Thomas appointed Dr. Thomas Bond to serve alongside Dr. Zachary.

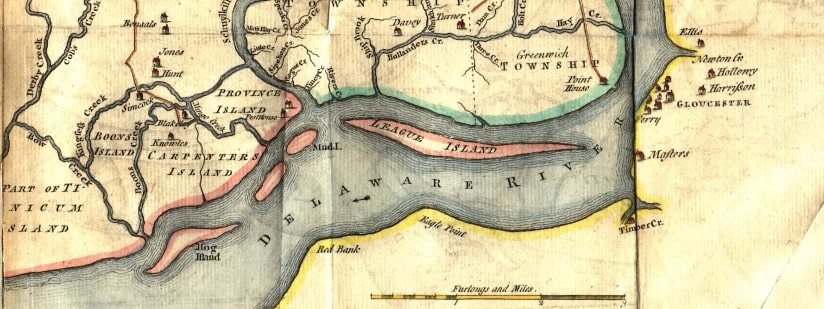

On February 3, 1742 Fisher’s Island, a 342-acre island at the mouth of the Schuylkill was purchased for 1,700-pounds from the executors of John Fisher’s estate to establish a quarantine hospital to isolate and shelter persons arriving by sea with epidemic diseases. The island was renamed Province Island (and is currently State Island.) The 1743 Act that allowed for the creation of the lazaretto was the first in Pennsylvania and required “that the nursing, medicine, maintenance and other necessaries should be defrayed by the importer, who was to give bonds for the faithful performance of his obligations, and in the event of a failure, he was to be committed to prison without bail … until he conformed.” As with the earlier law, no patient could be discharged without a health certificate from a doctor. There were also penalties for harboring a sick person who had been ordered to the pest house. The first physicians to the lazaretto were Drs. Bond and Zachary, but Zachary resigned soon after his appointment and from 1743 to 1754 Dr. Graeme was again serving, along with Dr. Bond, in this capacity. In response to the yellow fever outbreaks in the 1790s, a new lazaretto was built in 1799 about 6 miles away in Tinicum Township, and still stands. The original lazaretto on Province Island no longer exists.

There are many recorded instances of Graeme and Bond taking their responsibility seriously and detaining ships throughout the time they served. In January 1744 a ship from the Mediterranean, where plague was present, sailed directly into the port without stopping for inspection. Her captain was imprisoned for violating the laws and for using “abusive language.” Once detained, Drs. Graeme and Bond made a careful examination of the ship and passengers, determined all to be healthy, and the captain was released from jail with a stern warning; other captains were again warned of the penalties of violating the law against bringing ships from sick ports directly into Philadelphia. In 1747 Philadelphia was visited for the third time by yellow fever. In September the Eurydale arrived from Barbados, where the fever was raging when they set sail. One crew member had died enroute and one passenger was sick, so the ship was ordered to quarantine on arrival, but many of the passengers disembarked illegally and went into the city anyway, possibly starting the epidemic. (People were jerks back then too.) In September of 1749 the Francis and Elizabeth arrived from Rotterdam carrying passengers with “eruptive fever” (spotted fever, a tick borne bacterial infection). Doctors Graeme and Bond quarantined them and sent the sick passengers to the lazaretto on Province Island and the well were detained on board until it was sure they would not also become sick or bring contagion to the city.

Because the crowded and unsanitary conditions found aboard ships, which were often at sea for 60-90 days, were thought to be responsible for much of the illness seen in passengers, a new law was enacted in 1750 to limit the numbers of passengers importers could crowd onto the ship. The law dictated the amount of space that needed to be allotted, in both length and breadth, for each passenger and required suitable provisions for the duration of the voyage. This was supplemented in 1765 when the height to be allowed for each passenger was also specified, along with requirements that each ship carry a surgery kit and medicine chest and that the crew clean and fumigate the vessel periodically during the voyage.

While Graeme and Bond normally worked with inbound ship passengers, in 1754, officials in Pennsylvania were concerned about contagion being spread throughout the German areas of the city, and appointed them to investigate. They reported their findings in “Report of Doctors, Novr 16, 1754.” Perhaps still wary of the accusations of dereliction of duty leveled against him in 1740, the report makes a point of defending the actions taken regarding various ships that had been allowed into the port just prior to the outbreak. They noted that they had observed “ship fever” (epidemic typhus, a vector borne bacterial infection caused by lice often found on the rats and mice common in the crowded and unclean conditions aboard ship) which was common, and that they had taken precautions to nurse those suffering from it, but pointed out that they had never found the disease to be contagious once the afflicted were removed to more healthful conditions. They also reported that a recently landed ship had concealed illness from them by pretending to run aground before their check point so that ill passengers could be removed and thus everyone appeared to be in healthful condition when they made their visit and thus it was not their fault if sick passengers were missed. They ended their report by throwing blame back on the legislature: “our Case is really hard, since a Security from contagious Diseases is expected from us, and the Legislature has not made the necessary Regulations to prevent malignant Diseases being generated by these people, after they come into Port, where there is much more Danger of it than at Sea.”

1754 was the end of Dr. Graeme’s work in the port, although I could not find any specific reason why he left. His health was declining by this point and Pennsylvania Hospital had been founded a few years earlier by his colleague Thomas Bond, to which he served as a consulting physician, so it likely was just time for him to move on to a less strenuous form of practice after more than 20 years serving at the port.

Sources and Additional Reading

“A Colonial Health Report of Philadelphia, 1754.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 476-479. 1912.

Finger, Simon. The Contagious City: The Politics of Public Health in Early Philadelphia. Cornell University Press. 2012.

Jewel, MD, Wilson. Address Delivered before the Philadelphia County Medical Society. TK and PG Collins, Printers. 1857.

“Lazaretto Quarantine History.” www.ushistory.org

Scull, N. and Heap, G. Atlas of Delaware County. 1753.