Lost Objects: Elizabeth’s Family Tree Pin

The Graeme family was very well-to-do, and therefore had many fine things in the way of furnishings, tableware, decorative objects, and clothing, jewelry and accessories. Some of these things are listed in the various inventories that were taken of the house and its contents and some are described in The History of Montgomery County, by Theodore Bean. At the time the History was published (1884) some of these items were owned by descendants of Elizabeth’s niece Anny and shown to the author.

One object described in detail was:

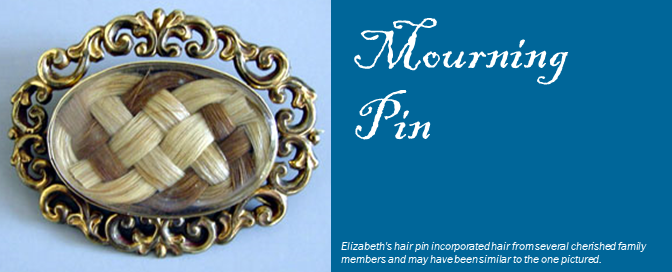

“…a family tree composed of hair within a glass, surrounded with rubies, all set in a case of gold, which was worn by Mrs. Ferguson [sic] as a breastpin. Its form was oval, one by one and a half inches in size. On its back was engraved: “the hair of Lady Ann Keith, Ann Graeme, Ann Stedman, and Jane Young. For E. Graeme 1766.””

Elizabeth would have been about 29 years old when she received this sentimental remembrance of her grandmother, mother, and two older sisters, all of whom had likely passed on (Ann who died March 3, 1766 was the last of the four women to pass).

Mourning jewelry is often associated with the Victorian-era, as Queen Victoria helped to popularize it when she began wearing it after the death of Prince Albert, but it was not uncommon from the Middle Ages through the early 20th century. It often consisted of a locket or glass fronted frame with the hair woven into a background pattern, braided, or arranged in an intricate pattern—often hair from multiple loved ones was included, as it was in Elizabeth’s pin. The other style commonly seen involved weaving individual strands into mesh-like beads and baubles or into a rope-like “chain” which could be worn as a necklace, bracelet or to attach a pocket watch. Men also wore hair jewelry in the form of these watch fobs or as cuff links.

As in any era, there were dishonest persons who would substitute the hair of your loved one with horse hair or other “generic” hair that was easier to work with, so you needed to make sure you worked with a reputable artisan!

So what became of Elizabeth’s pin? It first passed to her niece, Anny Young Smith (the daughter of her sister Jane Young) and from Anny to her son Samuel F. Smith. It was inherited by the Smith’s daughter, Mrs. Henry Chrystie Turnbull and was in her possession when it was shown to Theodore Bean, along with the family Bible, portraits, and other items in 1856. If Bean’s dates are correct, these items fortunately all survived the 1847 fire at Mrs. Turnbull’s mansion. Research needs to be done or contact reestablished with descendants to see if the pin and other items were also passed down to them and where they may have gone after. In 1985, when photographic reproductions of the portraits were made for the Keith House, it was still the descendants of Anny Young Smith who owned the originals and the Commonplace Book containing Elizabeth’s and Anny Young’s poetry, which was donated to Dickinson College, also sometime in the 1980s.